On curiosity-driven research (EN)

Professor Jo Vandesompele discuss about curiosity-driven research

I didn’t want to steal Jasper’s moment, but thought it was important to reiterate what he eloquently wrote in his thesis discussion on hypothesis-free or curiosity-driven research. But what is this exactly? Isn’t every scientist curious? Yes, but curiosity-driven research is different in many aspects. No grant must be written with a framed story in 3 parts, so-called work packages, each with its own hypothesis, methods, and risk mitigation strategy. Such a grant is typically evaluated by other scientists who decide whether it’s a good idea and if the team is capable of executing the plan. Many who know me also know that I’m a big advocate of a completely different system of distributing research money, a so-called lottery-among-equals, whereby only an assessment is made if the grant proposal makes sense, and passes basic criteria, after which faith decides whether you get the money or not. This system solves 2 problems. First, it no longer requires a holy belief that scientists can effectively compare and rank other scientists’ research proposals in an objective and predictive way. There is a lot of scientific evidence that we just can’t - as a starter read the book Noise by Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman. Caveat, you may no longer want to be part of an evaluation committee. Secondly, it fully supports curiosity-driven research.

Another way of achieving this goal is by providing basic funding to all researchers, a laudable effort at our own university, but then the sum must be sufficiently large, which unfortunately is not the case to date. I hope we’ll continue along this path and appreciate the benefits over competitive research funding.

Without such a novel system of distributing research money, Pieter Mestdagh and I wanted to give curiosity-driven research a chance in the OncoRNALab because we had many ideas without a coherent plan.

Let’s just try and see what works and what does not, and why not. And if we want to, switch topics or strategies overnight.

Indeed, curiosity-driven research, lottery-among-equals, and basic research funding require trust in the capability of the lab and the scientists that they will make the right decisions and spend the money wisely.

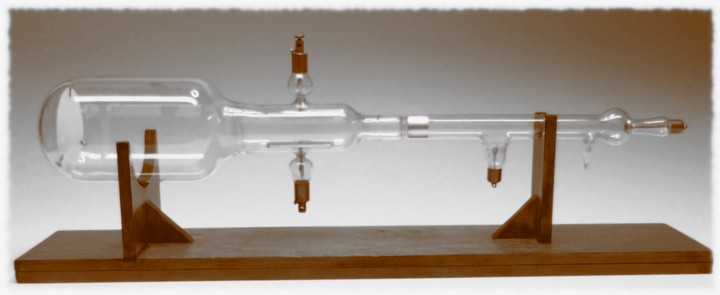

There are many historic examples of successful curiosity-driven research. One is the development of the cathode ray tube (see image on top): a glass vacuum tube on which high voltage is applied. It had no purpose, other than sheer curiosity what such a device would do. First, it was discovered that unknown rays were emitted, and later these rays were shown to be deflected by electric fields and magnetic fields. J.J. Thomson succeeded in measuring the mass-to-charge ratio, and showed that they consisted of negatively charged particles smaller than atoms. The electron was identified! The rays were called X-rays and their utility for medical imaging was rapidly realized. The same technology later developed into the first CRT television and electron accelerators for radiotherapy.

All these solutions and technologies would never have been invented if it was not for the sheer curiosity of making and exploring a basic cathode ray.

Of course, one has to be prepared to see and embrace the luck. Louis Pasteur had it right when he said (in French):

Chance favors the prepared mind.

I’m so grateful that Jasper was willing to embark upon such a journey, without a fixed plan or schedule. Just grit, curiosity, and commitment to explore.

What are your thoughts on curiosity-driven research?

Elfride De Baere, Patrick Calders, Kris Gevaert, Piet Hoebeke, Hans Van Vlierberghe, Ignace Lemahieu, Dirk De Craemer